Always Tomorrow

Moonah Arts Centre, Lutruwita/Tasmania

20 October - 11 November 2023

Always Tomorrow

Simon Crosbie

Julia Drouhin

David Greenhalgh

Amber Koroluk-Stephenson

Leigh Rigozzi

Lisa Sammut

Dylan Sheridan

Always Tomorrow explores speculative imaginings for The Future. Presented through a cross section of textile, painting, sculpture, installation and video, this exhibition explores the possibilities and contrasting affects of hope and despair, the tangible and unknown, comedy and tragedy, dreams and nightmares, collapse and renewal, looking towards The Future where the end is not the end.

Photography by Rosie Hastie

You Never Know How The Past To Come May Turn Out

Written by Nancy Mauro-Flude, October 2023

‘Whose beginning is not, nor end cannot be…’ is a sentence translated from a succession of conversations with angels by magus John Dee (1527-1609), Renaissance scholar, mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, occultist and consultant to Queen Elizabeth I. The records of these angelic conversations provide evidence of an eschatologically heightened period of extraordinary natural occurrences: exceptionally bright comets, earthquakes, and observations of new stars—copious references to an apocalypse. Nevertheless, five centuries later, in an era of intensified fervour, many people are driven by compulsion and possessed by the forward march to an endpoint in a so-called future.

Anticipating predicaments can be overwhelming amid the rising tides of our planetary climate emergency that is aided by the sweltering barricades of data farms that consume millions of litres of water to cool the storage of discs in the ‘cloud’ that comprises of digital storage, including Google’s Gmail for retrieval on demand anytime anywhere. These cryogenic data chambers allow K-pop members to post pictures of Banksy murals painted on the illegal separation wall in the occupied West Bank on Instagram (with no comments). As heirloom seeds are privately hoarded, bio-diversity loss continues. Even if the multitude of philosophical and socio-political contingencies are deemed unnecessary, I speculate that it’s the follies of a devastated biosphere that our ancestors to come are least likely to excuse us.

There are no ready-made resolutions, yet conceptualising how things aren’t inevitable –minute artistic acts– may be more potent and valuable than many realise. The exhibition ‘Always Tomorrow’ takes on this notional task, an assembly of six artists “brought together to experience renewal, looking towards The Future where the end is not the end” by Amber Koroluk-Stephenson, contains energetic artworks that do not display fear of desolate ineptitudes nor the gratification of optimistic solutions.

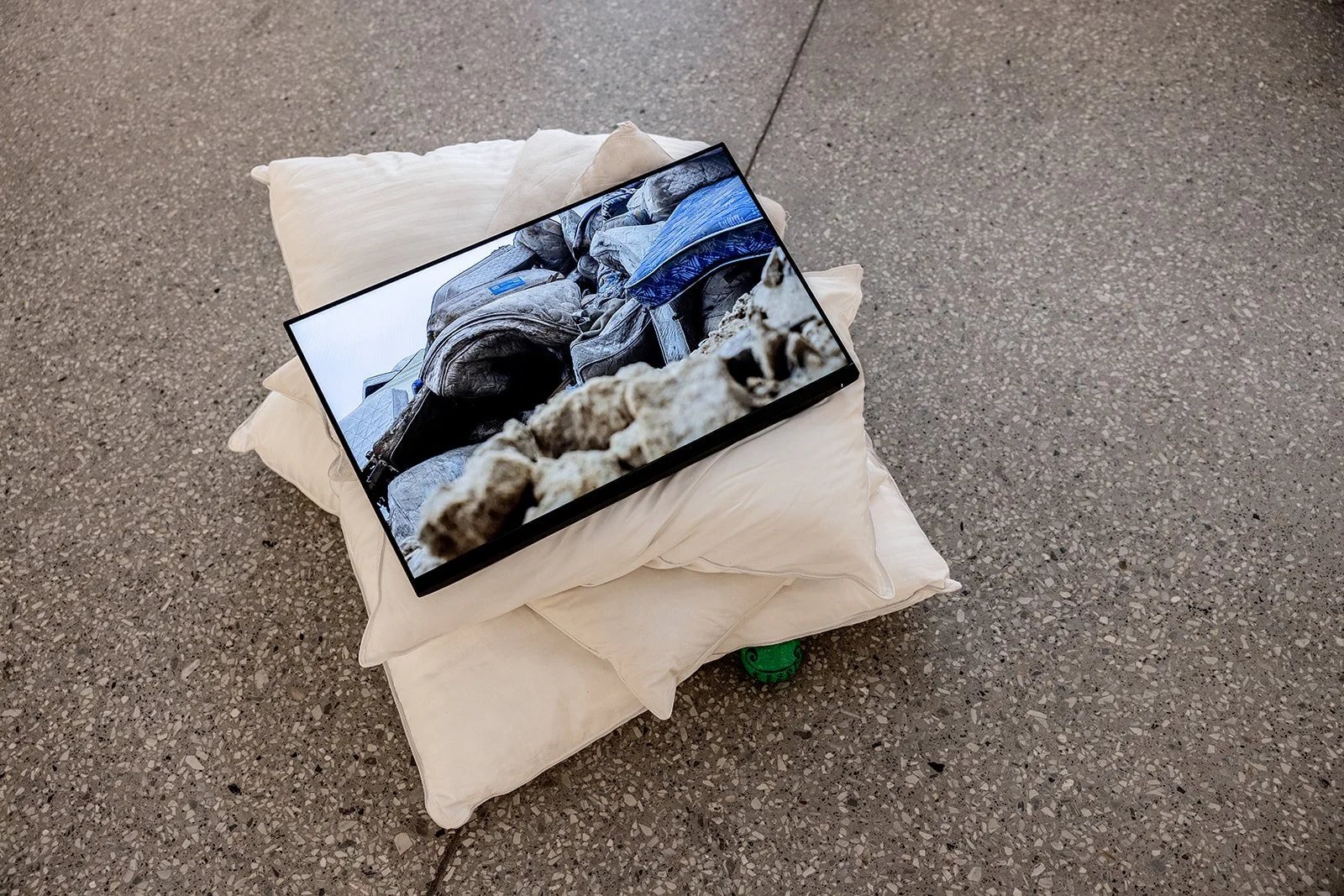

This conceptual premise is evident in the detritus of reveries offered in Bed Bug Bouncy Castle (2020) by Julia Drouhin—a video looping landscape of discarded mattresses alludes to an accretion of dreaming bodies. Restorative places of rest, beds are a healing stratum, a haven for microorganisms, a repository for rapture, or difficult things; sites for nocturnal rewriting.

Scarcely cherished for their resourcefulness, it is often artists who ask the hard questions through their work, inferring to the paragons: who does the tedious jobs of cleaning, who sorts through the garbage, who recompiles, and salvages discarded imaginings. In best-case scenarios, artworks can change the destinies of residues and remains of waste.

Simon Crosbie provides a subtle substantiation, 1965 (2016) stages a trio of golden woollen jumpers strung out and suspended in an empty living room. A trinity of windows underscores the eerie powers of the familiar. A disembodied performance of apparel and elongated arms that tendril accentuate how sartorial textiles both sheath and assist the wearer's ability to connect to an atmosphere where hope springs eternal. Transmitting alterities for the viewer to further contemplate.

What happens at one scale or angle may look and feel very different from what happens at another. Unfolding multiple realities in pulse study 11 (2023), Dylan Sheridan designs an in-situ distinctively alterable system of maladroit paraphernalia. As the installation co-mingles and clumsily improvising through permutational procedures, on-the-fly entities signal and beckon, making their energetic capacity kinaesthetically felt. These automated interactions form a capricious perceptual arena.

A choreography of uncanny objects and topographies features in the artworks of Amber Koroluk-Stephenson. Wishbones (separates) (2022) are sculptural abstractions of animal detritus. The elements draw us in to a world dramatically out of sync. The artwork titles gesture to talismans typically encountered during a Sunday roast, forking chicken bones spied drying out on the kitchen mantle to awaiting a starring role in the pulling and breaking divination. Instead, Koroluk-Stephenson’s oil painting Allegory for a Wishbone (2022) challenges the viewer’s propensity to suspend disbelief is contested. The tableau vivant is marked by stage curtains opening to a misé en scene: a full moon rises above a yacht sailing on an even passage at dusk. Held aloft by a skeletal motif, whalebone remains are precariously arranged on a central axis, situated on geometric floor tiles. This texture suggests a synthetic game engine, but the infinite scroll is disrupted by the raw geologies of stones. Relentless bushfires disrupt the boundaries between what is commonly identified as physical and material and virtual space, effectively mediating these divisions.

As my eyes linger, it strikes me that Koroluk-Stephenson uses herself as a subject in her theatrical compositions without the conceit of self-portraiture. Ruminating on natural habitats: “What is often called Nature is simply nonhuman designed things”, writes the eco philosopher Timothy Morton, who recommends scraping such slavish divisions.

This perspective is further revealed in how the Moon — the Earth's only nonhuman designed satellite — is escorted by synthetically engineered orbs that transmit and record or become merely the flotsam and jetsam of obsolete space junk, supporting the notion that the past is all around us. Lisa Sammut offers a poetic penumbra in her *sigh* series (2023). A set of collages share appealing images of our celestial hall of cosmic bodies playing its part in the terrestrial life of our planet. The Moon shines a guiding light on that which is ambiguous, which only adds to the radiance.

These phases are frequently associated with fertility rites in many cosmological mythologies of cultures. The Ngarrindjeri First Peoples (of the River Murray) recognise the crescent moon as the transfiguration of a waxing fecund womanly existence into an ethereal presence during this waning.

An aesthetics that lends itself to particular these transmutational processes is key to deciphering omens swathed in the affectionate attention of mystery. David Greenhalgh's evaporate this weight (2023) presents a montage of synthetic ambiences and vestiges that ebb and flow. In his video collage, a prism of light is overawed, yielding to tenuous incandescence, loamy particles of elegiac characters leak into membranes, the letterings continue to hover and glow through the interior space, an assemblage of enigmatic yet luminous contours and fuzzy verges brim with life energy.

Veracity tremors through a trio of large canvases displaying bold discharges of hi-vis text layered on terraformed successions of curves, lines and coatings. And So On (after Roger Imms) (2023), And Then (after Roger Imms) (2023), The Best of All Possible Worlds (after Roger Imms) (2023) by Leigh Rigozzi. Missive graphic striations contest their absorption as a literary artifice and are instead held by a nautical matrix derived from experiments in the spatial field; a series of found seascape paintings locally obtained at a deceased estate.

These are some of the ways in which I witness how the artworks that form the subjects of the exhibition veer away from essentialist queries of origin which is often considered to be common sense. The assortment of plurally produced works reveals insights into artistic research processes: site-specific installation, dramatic oil paintings, compositions of found objects, synthesised with domestic interventions, performances of terrestrial orbits, faerie tale wreckage and video loops of celestial bodies, all communicate sociocultural procedures and planetary structures; which contain the distinctive capacity to reach outside visual reference systems to deliver contiguous meaningmaking.

Put simply, to make an artwork that designs a world—in which change happens—showing how things can be transfigured otherwise is a necessary part of the difference between what things are potentially and how they merely seem. Now, when I hear Bob Dylan’s refrain, ‘You never know how the past will turn out,’ I can understand more readily how being present is a hallowed form of beholding the ancient future.

Notes

Duane W. Hamacher and Ray P. Norris (2011) Eclipses in Australian Aboriginal Astronomy, Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage 14(2):103-114.

Timothy Morton (2019) Journal of Futures Studies 23(4):97–100.

Deborah Harkness (1999) John Dee's Conversations with Angels: Cabala, Alchemy, and the End of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.